I'm a radical. For some reason, I don't seem to be able to go with the flow with anything.

The latest victim of my folly is muslin fabric, the plain jane material used to make toiles/muslins/test garments in sewing. Traditionally, unbleached cotton muslin is used straight off the bolt (with a pit-stop at the pressing station if you're fussy). Not me. I wash mine first.

You're probably rolling your eyes at that last sentence, wondering why on earth I would add a step to a process most people skip because they think sewing test garments is too time-consuming and tedious. I have my reasons, two in fact.

The first: Sizing is added to muslin during the manufacturing, which stiffens the fabric considerably. It's difficult to get a feel for the fit and appeal of a garment when it looks like it's been made out of construction paper. Run a length of muslin through the washer and dryer, and it turns into real fabric with drape and texture. It gives on the bias, and follows the body's curves instead of standing away stiffly.

And second: Things made with straight-off-the-bolt cotton muslin are not intended to be worn. Unwashed muslin is meant to be part of the pattern-making process, never an end product. It may live forever in the pattern file, but it will never find life outside the workroom. It can't be worn because it can't be washed. First time the completed garment hits the wash-water, it will shrink and shape-shift, rendering it unwearable.

Not being able to wear a muslin garment probably doesn't matter to most people. It's expendable, a means to an end. But the more I sew, the more uncomfortable I am with the idea of making disposable garments on purpose. What a waste of time, resources, and effort. So un-green!

Washed muslin is an attractive fabric. A little plain, perhaps, being cream-coloured and without pattern. If it's an everyday garment (and not a fancy-smancy dress), it could go into your wardrobe rotation as a neutral. Or something to wear when gardening, or at the beach.

To be honest, not many of my muslin test garments remain intact enough to wear. Most are so chopped and altered, they'd be indecent to don in public. In that case, I'm fine sending the remains to the rag bag, the fabric has served its purpose and I can let it go.

It's the garments that are basically intact that prick my conscious. They look like a regular dress/skirt/shirt/pant; their only sin is being made in an utilitarian fabric.

Lady T

Sew Lady Sew!

Thursday, January 14, 2016

Friday, November 29, 2013

Ick!

|

| Seam ripper. Friend or enemy? Frienemy? |

Alas, that's what spewed from mine yesterday when I inspected the single welt pocket on the upper left front of Studmuffin's jacket, aka the breast pocket or the hankie pocket. Instead of a smooth insertion, I had a lumpy, bumpy mess.

One of my primary goals when sewing is to make things that look nice. Not perfect, mind you, just nice. If it looks nice, I am happy. (And not the-man-on-horseback-glancing-your-way-as-he-gallops-by kind of nice. More the it-passes-casual-observation level of nice.) This was not nice. The fabric around the pocket was puckery and stressed.

I hate how welt pockets are made. The "sew two parallel lines, then cut a Y shaped hole between them and flip everything to the inside" technique makes me uncomfortable. The whole thing rests on the fabric not fraying, as there isn't any stitching on the ends to hold threads in check. There are alternate construction methods for double welts, but I haven't found any for the single welt.

An aside: Another sewing philosophy/attitude I have is: Think For Yourself. That's a rather harsh sentiment for many people, so I try to pretty it up by saying: You Are The Boss of Your Own Sewing. But they are two sides of the same coin. Just because the pattern instruction/tradition/your fav sewing guru tells you to do a something a certain way doesn't mean you have to - or should.

Think about what you're creating. Does the suggested way make sense? The tingle of uncertainty or unease is your subconscious' way of telling you Uh-uh! No thanks! Danger Will Robinson! (The last one is from Lost in Space, a tv show I watched with annoying regularity as a child. It's amazing what sticks in your brain.)

I ignored my tingle. I know better. I know better. But I did, because who am I to poo-poo the traditional methods of tailoring.

I'm Lady T, of course. The Boss of My Own Sewing. Once I thought about it, two alternative ways of constructing this thing popped into my mind. Two, not just one.

Today, I have to pick out that woeful pocket. I'm hoping I can rework it, making the opening a teensy bit bigger. Otherwise I'm going to have to recut the front, fuse it, thread trace it, blah, blah, blah all over again. I'm very lucky I have enough fabric left over (barely!) to have this option.

Who is the boss of your sewing? You? Or tradition?

Till next time,

Lady T

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

Stage One - Done!

|

| The upside-down left front jacket piece. Interfaced with P/P Tailor, with another layer for chest piece. Roll line taped. |

Pictured is the left front piece of Studmuffin's jacket. (upside-down)

The entire piece was interfaced with Palmer/Pletsch Perfect Fuse Tailor. An extra layer of interfacing, cut on the bias, was added as a chest piece. On custom tailoring, a third layer is usually added, but this seemed like enough structure. Time will tell.

The roll line was taped with fusible Japanese 1/4" tape. After fusing, I hand-stitched it in place. While I'm sure it would've bonded well to fabric, I'm not so sure how well it would've stayed attached to the soft, fuzzy interfacing layer below. Since Studmuffin wears jackets on a daily basis, this one (if it fits!) will see a lot of use.

The breast pocket and welt pockets were thread-traced to make them visible on the front, along with the center front line. These loose, long basting stitches were done in a jiffy by hand. I could've machine basted them, but hand basting is easier to remove and doesn't take long to do.

Little thread dots highlight The Dot (so named by Palmer/Pletsch for the uber important notched collar marking) and other necessary sewing guides. Seam notches have been marked with tiny snips in the seam allowance.

The front waist dart is pinned. I marked the legs with a pencil, which was beginning to fade, so I formed the dart right away before it disappeared.

The lining is cut and marked. I'm all set to go.

On to Stage Two!

Till next time,

Lady T

Tuesday, November 26, 2013

Fusing Interfacing

I have two hard-and-fast rules for fusible interfacing:

1. Use high quality interfacing.

2. Make double-sure every bit of the interfacing is fused onto the fashion fabric.

As long as I abide by these two rules, I've had great success. No bubbles, no regrets.

High quality interfacing isn't easy to find. Usually I have to mail order it from Pam Earny at Fashion Sewing Supply (this link takes you to the American site, I have to click on the Canadian/International section) or Palmer/Pletsch or Sawyer Brook. When I'm in Ottawa, I pick up some at Daryl Thomas Textiles.

High quality interfacing costs $$. The base fabric is often pre-shrunk. The adhesive is distributed evenly in a fine coating instead of thick beads. Inferior interfacing can make expensive fabric look cheap. High quality interfacing can make inexpensive fabric look lux. To me, it's worth every nickel.

Fusing interfacing takes time. Lots and lots of time. At least the way I fuse does.

A few years ago, Daryl from Daryl Thomas told me not to use steam when fusing interfacing to fashion fabric. I was flabbergasted - everyone knows you need plenty of steam and heat to make that sucker stick! He said you don't want moisture forming a barrier between the fabric and the interfacing when fusing. Use all the steam you want after the initial bonding, but use a dry iron first. Even though the idea was radical, Daryl's explanation made sense, so that's what I do.

I hate the gooey residue that sticks to irons and ironing board covers when interfacing overhangs/peeks out beyond the edge of the fashion fabric. Marta Alto, in the Palmer/Pletsch Jackets for Everybody dvd, shows how to cut interfacing so it is marginally smaller than the garment piece it will be attached to. She cuts part way around the pattern, then "scoots" it over the cut section to reduce the size and finishes cutting. Marta makes it look easy, but so far I haven't tried it. I like pins, and grainlines, and knowing exactly what the finished size will be, and how much interfacing I'm using. Her way would stress me out. (Yes, I'm a control freak.)

To keep any overhanging interfacing from adhering where I don't want it, I layer the piece being fused between two pieces of paper, like a ham and cheese sandwich.

My fuse sandwich:

paper

interfacing, glue side facing down

fabric, wrong side facing up

paper

The paper underneath protects the ironing board cover, and the paper on top protects the iron. When fusing, I never ever leave the iron unattended. Too risky! Scorch marks would be the least of possible problems. If left long enough, you could actually burn the paper. (Note: This is the way I fuse. I'm not saying it's the right way and that you should do it. Try it at your own risk. And if you do, for heaven's sake, pay attention! Hot irons require due diligence!)

Before you start fusing, it makes sense to assemble test samples from scraps. Once your samples have cooled, check how well the interfacing and the fabric have bonded. Can you peel off the interfacing? Try fusing it again. Some interfacings work better with some fabrics. Once your sample has passed the fuse-ability test, check to see if the interfaced scrap has the suppleness or body you require. There are tons of different types of interfacing and another one may do the job better.

Onto fusing the actual garment. The first pass is with a dry iron. No steam. Depending on the interfacing and the fashion fabric, it usually takes between 5-15 seconds to activate the adhesive. (Establish how long it takes when making the sample.) Use a watch to time it - fusing is boring and it's too easy for your brain to imagine 10 seconds have passed when in reality, only 3 seconds have.

Once the entire piece has been fused, I spritz the paper with water from my spray bottle (that never gets used for anything else). The paper is visibly wet. With the iron set on steam, I go over the entire piece a second time. Clouds of steam float up. It's easy to see where you've been because the paper starts to dry.

If I'm at all concerned that I might have missed a spot, I go over it again. I really, really want the interface to bond with every fiber of the fashion fabric.

Fusing Tips

1. Lift the iron when moving it to a new location, don't slide it. Sliding may shift the fabric and/or interfacing, causing distortion.

2. Once fused, let the fabric cool completely before moving. The bond is not complete until the fabric is cold.

3. Or use the time while the fabric is cooling to add shape. For example, while the interfaced fabric is still warm, wrap a collar around a pressing ham. As it cools, the interfacing will "set" with this shape.

4. Test scraps can be sewn together (creating a seamed edge and double layer) and used to practice making buttonholes.

Once upon a time, I avoided fusible interfacing. I hated both the end results (bubbles) and the mess (gooey bits). Now that I've figured out solutions to both those problems, I love the finished product and ease of using quality fusible interfacing. What about you? Are you a sew-in interfacing type of person? Or do you use fusible? Or do you forsake interfacing all together?

Till next time,

Lady T

1. Use high quality interfacing.

2. Make double-sure every bit of the interfacing is fused onto the fashion fabric.

As long as I abide by these two rules, I've had great success. No bubbles, no regrets.

High quality interfacing isn't easy to find. Usually I have to mail order it from Pam Earny at Fashion Sewing Supply (this link takes you to the American site, I have to click on the Canadian/International section) or Palmer/Pletsch or Sawyer Brook. When I'm in Ottawa, I pick up some at Daryl Thomas Textiles.

High quality interfacing costs $$. The base fabric is often pre-shrunk. The adhesive is distributed evenly in a fine coating instead of thick beads. Inferior interfacing can make expensive fabric look cheap. High quality interfacing can make inexpensive fabric look lux. To me, it's worth every nickel.

Fusing interfacing takes time. Lots and lots of time. At least the way I fuse does.

A few years ago, Daryl from Daryl Thomas told me not to use steam when fusing interfacing to fashion fabric. I was flabbergasted - everyone knows you need plenty of steam and heat to make that sucker stick! He said you don't want moisture forming a barrier between the fabric and the interfacing when fusing. Use all the steam you want after the initial bonding, but use a dry iron first. Even though the idea was radical, Daryl's explanation made sense, so that's what I do.

I hate the gooey residue that sticks to irons and ironing board covers when interfacing overhangs/peeks out beyond the edge of the fashion fabric. Marta Alto, in the Palmer/Pletsch Jackets for Everybody dvd, shows how to cut interfacing so it is marginally smaller than the garment piece it will be attached to. She cuts part way around the pattern, then "scoots" it over the cut section to reduce the size and finishes cutting. Marta makes it look easy, but so far I haven't tried it. I like pins, and grainlines, and knowing exactly what the finished size will be, and how much interfacing I'm using. Her way would stress me out. (Yes, I'm a control freak.)

To keep any overhanging interfacing from adhering where I don't want it, I layer the piece being fused between two pieces of paper, like a ham and cheese sandwich.

My fuse sandwich:

paper

interfacing, glue side facing down

fabric, wrong side facing up

paper

The paper underneath protects the ironing board cover, and the paper on top protects the iron. When fusing, I never ever leave the iron unattended. Too risky! Scorch marks would be the least of possible problems. If left long enough, you could actually burn the paper. (Note: This is the way I fuse. I'm not saying it's the right way and that you should do it. Try it at your own risk. And if you do, for heaven's sake, pay attention! Hot irons require due diligence!)

Before you start fusing, it makes sense to assemble test samples from scraps. Once your samples have cooled, check how well the interfacing and the fabric have bonded. Can you peel off the interfacing? Try fusing it again. Some interfacings work better with some fabrics. Once your sample has passed the fuse-ability test, check to see if the interfaced scrap has the suppleness or body you require. There are tons of different types of interfacing and another one may do the job better.

Onto fusing the actual garment. The first pass is with a dry iron. No steam. Depending on the interfacing and the fashion fabric, it usually takes between 5-15 seconds to activate the adhesive. (Establish how long it takes when making the sample.) Use a watch to time it - fusing is boring and it's too easy for your brain to imagine 10 seconds have passed when in reality, only 3 seconds have.

|

| Interfacing sandwich dampened with spray from water bottle. Iron leaves a map of where it's pressed. |

Once the entire piece has been fused, I spritz the paper with water from my spray bottle (that never gets used for anything else). The paper is visibly wet. With the iron set on steam, I go over the entire piece a second time. Clouds of steam float up. It's easy to see where you've been because the paper starts to dry.

If I'm at all concerned that I might have missed a spot, I go over it again. I really, really want the interface to bond with every fiber of the fashion fabric.

Fusing Tips

1. Lift the iron when moving it to a new location, don't slide it. Sliding may shift the fabric and/or interfacing, causing distortion.

2. Once fused, let the fabric cool completely before moving. The bond is not complete until the fabric is cold.

3. Or use the time while the fabric is cooling to add shape. For example, while the interfaced fabric is still warm, wrap a collar around a pressing ham. As it cools, the interfacing will "set" with this shape.

4. Test scraps can be sewn together (creating a seamed edge and double layer) and used to practice making buttonholes.

Once upon a time, I avoided fusible interfacing. I hated both the end results (bubbles) and the mess (gooey bits). Now that I've figured out solutions to both those problems, I love the finished product and ease of using quality fusible interfacing. What about you? Are you a sew-in interfacing type of person? Or do you use fusible? Or do you forsake interfacing all together?

Till next time,

Lady T

Sunday, November 24, 2013

Game Plan

The subtitle for this post could be: Am I Nuts?

Answer: YES!

Recently, I finished McCall's 6172, the Palmer/Pletsch tailored jacket pattern. It turned out quite well. So well, in fact, I reached into the pile of discarded projects from the summer and pulled out a grey tweed jacket I had cut out for my Studmuffin. I hoped to keep the jacket-making momentum going and whiz through this project, lickety-split.

It's hard to whiz when jacket-making. There's so much prep work to do! You'd think having the fashion fabric cut would mean I could leap into sewing, but alas, that's not so. There's interfacing to cut, then to fuse. Then all the pattern markings to transfer. Plus cut out the lining.

Anyway, I'm almost finished the prep work. Just the lining left. So Stage One of the Game Plan is almost done.

Then it's on to Stage Two - sewing the fashion fabric and lining.

And finally Stage Three - the hand finishing. Hem work and buttons. Final pressing.

So that's the official Game Plan. By thinking in stages, I hope not to get overwhelmed by the project. The goal is to whiz through each bit. I'd love to be finished by the end of the week. (hahaha!) We'll see.

Till next time,

Lady T

Odd aside: The title for this post was subliminal on my part. The Grey Cup game is on and the sound wafted over to me in a different room, settle into my brain, and influenced my thoughts.

Answer: YES!

Recently, I finished McCall's 6172, the Palmer/Pletsch tailored jacket pattern. It turned out quite well. So well, in fact, I reached into the pile of discarded projects from the summer and pulled out a grey tweed jacket I had cut out for my Studmuffin. I hoped to keep the jacket-making momentum going and whiz through this project, lickety-split.

It's hard to whiz when jacket-making. There's so much prep work to do! You'd think having the fashion fabric cut would mean I could leap into sewing, but alas, that's not so. There's interfacing to cut, then to fuse. Then all the pattern markings to transfer. Plus cut out the lining.

Anyway, I'm almost finished the prep work. Just the lining left. So Stage One of the Game Plan is almost done.

Then it's on to Stage Two - sewing the fashion fabric and lining.

And finally Stage Three - the hand finishing. Hem work and buttons. Final pressing.

So that's the official Game Plan. By thinking in stages, I hope not to get overwhelmed by the project. The goal is to whiz through each bit. I'd love to be finished by the end of the week. (hahaha!) We'll see.

Till next time,

Lady T

Odd aside: The title for this post was subliminal on my part. The Grey Cup game is on and the sound wafted over to me in a different room, settle into my brain, and influenced my thoughts.

Tuesday, November 19, 2013

Sew Inspiring

As you may have noticed, I've been in a sewing slump - a big, long one. For several months it seemed as if a black cloud hovered over my sewing room, its evil presence contaminating everything I touched.

When I had trouble with project after project, I realized the problem wasn't the pattern/sewing machine/instructions - it was me. My body might be in the sewing room, but my heart wasn't. So I put all the mangled bits in boxes, and didn't sew, saving bolts of beautiful fabric from eminent destruction.

This fall, I ventured back into my sewing space. While it was good to be there again, I felt I needed a little help reclaiming my creativity. Cue the Club BMV (Butterick, McCalls, Vogue) internet sale!

This is what I scooped up:

(Note: clicking on photos makes them larger)

Kwik Sew 3766, on the bottom, is a Kwik Start Learn to Sew pattern. This might seem like an odd choice, given I teach t-shirt classes. The appeal is it's a good basic design, with two neckline options, and easy instructions. I want to test it as a potential class pattern.

Kwik Sew 3915, on the left, has the prettiest ruched necklines. I love the detailing. It bumps the basic t-shirt to another level.

Vogue 8962, on the top, takes my breath away. The drawing on the envelope does not do it justice and doesn't even show the best part - the gorgeous back! Fortunately a photograph of the striped version was featured in their recent new pattern line-up, and I got to see it in all its glory. The stripes in the back are cut on the bias, and hang in a beautiful chevron. Drool. I lurve this one!

The white Anne Klein Jacket on the left, Vogue 1293, has the most beautiful seam-lines. Unfortunately the white fabric washes them out, so they're hard to see. Much to my surprise, this is an unlined jacket! Not even in the sleeves. Alas, the pants would not be flattering on me....

Vogue 8910, the jacket on the right, is cut on the bias. Every main piece, including the sleeves. I have a piece of a grey wool plaid that would make me look a little lumberjack-ish if sewn on the straight of grain, so I was delighted to find this pattern.

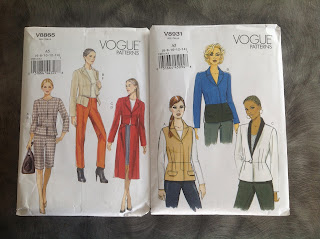

The peplum jackets! These two make my heart beat a little faster. Peplums are flattering on me. The little flounce creates shaping and makes my straight up and down torso look more feminine.

Vogue 8865, the pattern on the left, has shoulder princess seams with an optional zipper detail at the waistline. The zipper opening is weird (it opens sideways on the waist seam, not up and down along the front) yet oddly appealing. It's a "make you look twice" detail.

I have Big Plans for the one on the right, Vogue 8931, involving mottled blue/grey/green boiled wool fabric I bought from Sawyer Brook. By a fluke, the blue matches another piece of plain boiled wool I own. I see Version C of this pattern emerging from my sewing room...

So, dear reader, have you ever had to wrestle with your muse? Has your creativity ever deserted you? How did you bring yourself out of your sewing slump? I'd love to know.

Till next time,

Lady T

When I had trouble with project after project, I realized the problem wasn't the pattern/sewing machine/instructions - it was me. My body might be in the sewing room, but my heart wasn't. So I put all the mangled bits in boxes, and didn't sew, saving bolts of beautiful fabric from eminent destruction.

This fall, I ventured back into my sewing space. While it was good to be there again, I felt I needed a little help reclaiming my creativity. Cue the Club BMV (Butterick, McCalls, Vogue) internet sale!

This is what I scooped up:

(Note: clicking on photos makes them larger)

|

| 3 t-shirts, clockwise from bottom: KS3766, KS3915, V8962 |

Kwik Sew 3766, on the bottom, is a Kwik Start Learn to Sew pattern. This might seem like an odd choice, given I teach t-shirt classes. The appeal is it's a good basic design, with two neckline options, and easy instructions. I want to test it as a potential class pattern.

Kwik Sew 3915, on the left, has the prettiest ruched necklines. I love the detailing. It bumps the basic t-shirt to another level.

Vogue 8962, on the top, takes my breath away. The drawing on the envelope does not do it justice and doesn't even show the best part - the gorgeous back! Fortunately a photograph of the striped version was featured in their recent new pattern line-up, and I got to see it in all its glory. The stripes in the back are cut on the bias, and hang in a beautiful chevron. Drool. I lurve this one!

|

| 2 jackets with interesting style details: V1293 (seam-lines), V8910 (bias cut) |

|

| 2 peplum jackets - (left) V8865 with odd waistline zipper, (right) V8931 the pattern I have Big Plans for |

Vogue 8865, the pattern on the left, has shoulder princess seams with an optional zipper detail at the waistline. The zipper opening is weird (it opens sideways on the waist seam, not up and down along the front) yet oddly appealing. It's a "make you look twice" detail.

I have Big Plans for the one on the right, Vogue 8931, involving mottled blue/grey/green boiled wool fabric I bought from Sawyer Brook. By a fluke, the blue matches another piece of plain boiled wool I own. I see Version C of this pattern emerging from my sewing room...

So, dear reader, have you ever had to wrestle with your muse? Has your creativity ever deserted you? How did you bring yourself out of your sewing slump? I'd love to know.

Till next time,

Lady T

Monday, May 06, 2013

Does Size Matter?

Picking which size to use on a sewing pattern is a little like playing Pin the Tail on the Donkey. Without being able to see very well, you stab at something over and over with a pin, praying you get it right in the end. (Ha! Ha! Small joke.)

I gave up expecting a pattern to fit straight from the envelope years ago. Take in, let out (usually the latter), it's all in a day's sewing now. But which do you start with - a pattern that's too big or too small? Do you pick by high bust, full bust or the biggest body measurement?

There are as many theories for picking the proper pattern size as there are sewing gurus. If it was as simple as following the pattern's size chart, we wouldn't have this controversy.

My favorite (and the most accurate for me) is Nancy Zieman's method when using a Big 4 pattern (Vogue, Butterick, McCall's, Simplicity), outlined in her book, Fitting Finesse. For upper torso garments (shirt, jacket, coat), Nancy Z uses the cross chest measurement, from underarm crease to underarm crease. Her baseline is 14" = Size 14. With every half inch difference, the size correspondingly goes up or down. Like this:

12-1/2" = Size 8

13" = Size 10

13-1/2" = Size 12

14" = Size 14

14-1/2" = Size 16

15" = Size 18

As I said earlier, I like this method to pick a pattern size. It eliminates measurement distortions caused by narrow or wide backs.

This past Saturday, I taught a t-shirt fitting class to members of my sewing guild. I asked my students to take a leap of faith and pick their pattern size a la Nancy Zieman.

Convincing a busty woman to go down a pattern size or two is no mean feat! They know the center front of the larger pattern strains across center front, so no way would a smaller pattern ever fit!

And they're right. It won't.

How could it? Their full bust measurement is larger than the pattern's. To make it work, more room must be added via a full bust adjustment. Sometimes a broad back alteration is needed, too.

This raises an important question. If you have to add to a pattern to make it fit, why not start with a bigger pattern in the first place?

The answer can be found in the neckline and upper chest. A bigger pattern has a fuller upper chest. This results in gaping necklines and fabric bubbles above the high bust caused by too much material. Using a smaller pattern reduces the amount of fabric this area, letting the cloth rest closer to the body. Extra fabric is added where it is needed - the bust and sometimes the back.

Enlarging the middle of the torso is easier than shrinking the upper chest. (Reducing the collar and its seam can be a knuckle gnawing experience.) With the smaller pattern, the garment fits in the shoulder area - important when the garment hangs from the shoulders.

Is this method foolproof? Of course not. What in life is? Tweaking is needed. Sometimes lots of tweaking.

But I think it's a darn good place to start .

How do you pick your pattern size?

- Lady T

I gave up expecting a pattern to fit straight from the envelope years ago. Take in, let out (usually the latter), it's all in a day's sewing now. But which do you start with - a pattern that's too big or too small? Do you pick by high bust, full bust or the biggest body measurement?

There are as many theories for picking the proper pattern size as there are sewing gurus. If it was as simple as following the pattern's size chart, we wouldn't have this controversy.

My favorite (and the most accurate for me) is Nancy Zieman's method when using a Big 4 pattern (Vogue, Butterick, McCall's, Simplicity), outlined in her book, Fitting Finesse. For upper torso garments (shirt, jacket, coat), Nancy Z uses the cross chest measurement, from underarm crease to underarm crease. Her baseline is 14" = Size 14. With every half inch difference, the size correspondingly goes up or down. Like this:

12-1/2" = Size 8

13" = Size 10

13-1/2" = Size 12

14" = Size 14

14-1/2" = Size 16

15" = Size 18

As I said earlier, I like this method to pick a pattern size. It eliminates measurement distortions caused by narrow or wide backs.

This past Saturday, I taught a t-shirt fitting class to members of my sewing guild. I asked my students to take a leap of faith and pick their pattern size a la Nancy Zieman.

Convincing a busty woman to go down a pattern size or two is no mean feat! They know the center front of the larger pattern strains across center front, so no way would a smaller pattern ever fit!

And they're right. It won't.

How could it? Their full bust measurement is larger than the pattern's. To make it work, more room must be added via a full bust adjustment. Sometimes a broad back alteration is needed, too.

This raises an important question. If you have to add to a pattern to make it fit, why not start with a bigger pattern in the first place?

The answer can be found in the neckline and upper chest. A bigger pattern has a fuller upper chest. This results in gaping necklines and fabric bubbles above the high bust caused by too much material. Using a smaller pattern reduces the amount of fabric this area, letting the cloth rest closer to the body. Extra fabric is added where it is needed - the bust and sometimes the back.

Enlarging the middle of the torso is easier than shrinking the upper chest. (Reducing the collar and its seam can be a knuckle gnawing experience.) With the smaller pattern, the garment fits in the shoulder area - important when the garment hangs from the shoulders.

Is this method foolproof? Of course not. What in life is? Tweaking is needed. Sometimes lots of tweaking.

But I think it's a darn good place to start .

How do you pick your pattern size?

- Lady T

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)